by David Mertz, Ph.D. <[email protected]>

(see also Part Two of this tutorial)

IP sockets are the lowest level layer upon which high level internet protocols are built--every thing from HTTP, to SSL, to POP3, to Kerberos, to UDP-Time. To implement custom protocols, or to customize implementation of well-known protocols, a programmer needs a working knowledge of the basic socket infrastructure. A similar API is available in many languages; this tutorial focuses primarily on C programming, but it also uses Python as a representative higher-level language for examples.

Readers of this tutorial will be introduced to the basics of programming custom network tools using the cross-platform Berkeley Sockets Interface. Almost all network tools in Linux and other Unix-based operating systems rely on this interface.

This tutorial requires a minimal level of knowledge of C, and ideally of Python also (mostly for part two). However, readers who are not familiar with either programming language should be able to make it through with a bit of extra effort; most of the underlying concepts will apply equally to other programming languages, and calls will be quite similar in most high-level scripting languages like Ruby, Perl, TCL, etc.

While this tutorial introduces the basic concepts behind IP (internet protocol) networks, it certainly does not hurt readers to have some prior acquaintance with the concept of network protocols and layers.

David Mertz is a writer, a programmer, and a teacher, who always endeavors to improve his communication to readers (and tutorial takers). He welcomes any comments, please direct them to <[email protected]> .

David also wrote the book Text Processing in Python which readers can read online at http://gnosis.cx/TPiP/

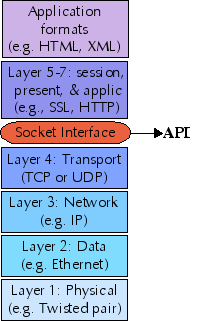

What we usually call a computer network is composed of a number of "network layers" , each providing a different restriction and/or guarantee about the data at that layer. The protocols at each network layer generally have their own packet formats, headers, and layout.

The seven traditional layers of a network are divided into two groups: upper layers and lower layers. The sockets interface provides a uniform API to the lower layers of a network, and allows you to implement upper layers within your sockets application. Further, application data formats may themselves constitute further layers, e.g. SOAP is built on top of XML, and ebXML may itself utilize SOAP. In any case, anything past layer 4 is outside the scope of this tutorial.

While the sockets interface theoretically allows access to protocol families other than IP, in practice, every network layer you use in your sockets application will use IP. For this tutorial we only look at IPv4; in the future IPv6 will become important also, but the principles are the same. At the transport layer, sockets support two specific protocols: TCP (transmission control protocol) and UDP (user datagram protocol).

Sockets cannot be used to access lower (or higher) network layers; for example, a socket application does not know whether it is running over ethernet, token ring, or a dialup connection. Nor does the sockets pseudo-layer know anything about higher-level protocols like NFS, HTTP, FTP, and the like (except in the sense that you might yourself write a sockets application that implements those higher-level protocols).

At times, the sockets interface is not your best choice for a network programming API. Specifically, many excellent libraries exist (in various languages) to use higher-level protocols directly, without having to worry about the details of sockets--the libraries handle those details for you. While there is nothing wrong with writing your own SSH client, for example, there is not need to do so simply to let an application transfer data securely. Lower-level layers than those sockets address fall pretty much in the domain of device driver programming.

As the last panel indicated, when you program a sockets application, you have a choice to make between using TCP and using UDP. Each has its own benefits and disadvantages.

TCP is a stream protocol, while UDP is a datagram protocol. That is to say, TCP establishes a continuous open connection between a client and a server, over which bytes may be written--and correct order guaranteed--for the life of the connection. However, bytes written over TCP have no built-in structure, so higher-level protocols are required to delimit any data records and fields within the transmitted bytestream.

UDP, on the other hand, does not require that any connection be established between client and server, it simply transmits a message between addresses. A nice feature of UDP is that its packets are self-delimiting--each datagram indicates exactly where it begins and ends. A possible disadvantage of UDP, however, is that it provides no guarantee that packets will arrive in-order, or even at all. Higher-level protocols built on top of UDP may, of course, provide handshaking and acknowledgements.

A useful analogy for understanding the difference between TCP and UDP is the difference between a telephone call and posted letters. The telephone call is not active until the caller "rings" the receiver and the receiver picks up. The telephone channel remains alive as long as the parties stay on the call--but they are free to say as much or as little as they wish to during the call. All remarks from either party occur in temporal order. On the other hand, when you send a letter, the post office starts delivery without any assurance the recipient exists, nor any strong guarantee about how long delivery will take. The recipient may receive various letters in a different order than they were sent, and the sender may receive mail interspersed in time with those she sends. Unlike with the USPS, undeliverable mail always goes to the dead letter office, and is not returned to sender.

Beyond the protocol--TCP or UDP--there are two things a peer (a

client or server) needs to know about the machine it communicates

with: An IP address and a port. An IP address is a 32-bit data

value, usually represented for humans in "dotted quad" notation,

e.g., 64.41.64.172 . A port is a 16-bit data value,

usually simply represented as a number less than 65536--most often

one in the tens or hundreds range. An IP address gets a packet

to a machine, a port lets the machine decide which

process/service (if any) to direct it to. That is a slight

simplification, but the idea is correct.

The above description is almost right, but it misses something.

Most of the time when humans think about an internet host (peer),

we do not remember a number like 64.41.64.172 , but

instead a name like gnosis.cx . To find the IP address

associated with a particular host name, usually you use a Domain

Name Server, but sometimes local lookups are used first (often via

the contents of /etc/hosts ). For this tutorial, we

will generally just assume an IP address is available, but the next

panel discusses coding name/address lookups.

The command-line utility nslookup can be used to

find a host IP address from a symbolic name. Actually, a number

of common utilities, such as ping or network

configuration tools, do the same thing in passing. But it is

simple to do the same thing programmatically.

In Python or other very-high-level scripting languages, writing a utility program to find a host IP address is trivial:

#!/usr/bin/env python

"USAGE: nslookup.py <inet_address>"

import socket, sys

print socket.gethostbyname(sys.argv[1])

The trick is using a wrapped version of the same

gethostbyname()) function we also find in C. Usage

is as simple as:

$ ./nslookup.py gnosis.cx

64.41.64.172

In C, that standard library call gethostbyname()

is used for name lookup. The below is a simple implementation of

nslookup as a command-line tool; adapting it for use

in a larger application is straightforward. Of course, C is a

bit more finicky than Python is.

/* Bare nslookup utility (w/ minimal error checking) */

#include <stdio.h> /* stderr, stdout */

#include <netdb.h> /* hostent struct, gethostbyname() */

#include <arpa/inet.h> /* inet_ntoa() to format IP address */

#include <netinet/in.h> /* in_addr structure */

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

struct hostent *host; /* host information */

struct in_addr h_addr; /* internet address */

if (argc != 2) {

fprintf(stderr, "USAGE: nslookup <inet_address>\n");

exit(1);

}

if ((host = gethostbyname(argv[1])) == NULL) {

fprintf(stderr, "(mini) nslookup failed on '%s'\n", argv[1]);

exit(1);

}

h_addr.s_addr = *((unsigned long *) host->h_addr_list[0]);

fprintf(stdout, "%s\n", inet_ntoa(h_addr));

exit(0);

}

Notice that the returned value from gethostbyname()

is a hostent structure that describes the names host.

The member host->h_addr_list contains a list of

addresses, each of which is a 32-bit value in "network byte

order"--i.e. the endianness may or may not be machine native

order. In order to convert to dotted-quad form, use the function

inet_ntoa() .

My examples for both clients and servers will use one of the

simplest possible applications: one that sends data and receives

the exact same thing back. In fact, many machines run an "echo

server" for debugging purposes; this is convenient for our initial

client, since it can be used before we get to the server portion

(assuming you have a machine with echod running).

I would like to acknowledge the book TCP/IP Sockets in C by Donahoo and Calvert (see Resources). I have adapted several examples that they present. I recommend the book--but admittedly, echo servers/clients will come early in most presentations of sockets programming.

The steps involved in writing a client application differ slightly between TCP and UDP clients. In both cases, you first create the socket; in the TCP case only, you next establish a connection to the server; next you send some data to the server; then receive data back; perhaps the sending and receiving alternates for a while; finally, in the TCP case, you close the connection.

First we will look at a TCP client, in the second part of the tutorial we will make some adjustments to do (roughly) the same thing with UDP. Let's look at the first few lines--some includes, and creating the socket:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#define BUFFSIZE 32

void Die(char *mess) { perror(mess); exit(1); }

There is not too much to the setup. A particular buffer size is defined, which limits the amount of data echo'd at each pass (but we loop through multiple passes, if needed). . A small error function is also defined.

The arguments to the socket() call decide the type

of socket: PF_INET just means it uses IP (which you

always will); SOCK_STREAM and IPPROTO_TCP

go together for a TCP socket.

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

int sock;

struct sockaddr_in echoserver;

char buffer[BUFFSIZE];

unsigned int echolen;

int received = 0;

if (argc != 4) {

fprintf(stderr, "USAGE: TCPecho <server_ip> <word> <port>\n");

exit(1);

}

/* Create the TCP socket */

if ((sock = socket(PF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_TCP)) < 0) {

Die("Failed to create socket");

}

The value returned is a socket handle, which is similar to a file handle; specifically, if the socket creation fails, it will return -1 rather than a positive numbered handle.

Now that we have created a socket handle, we need to establish a

connection with the server. A connection requires a

sockaddr structure that describes the server.

Specifically, we need to specify the server and port to connect to

using echoserver.sin_addr.s_addr and

echoserver.sin_port . The fact we are using an IP

address is specified with echoserver.sin_family , but

this will always be set to AF_INET .

/* Construct the server sockaddr_in structure */

memset(&echoserver, 0, sizeof(echoserver)); /* Clear struct */

echoserver.sin_family = AF_INET; /* Internet/IP */

echoserver.sin_addr.s_addr = inet_addr(argv[1]); /* IP address */

echoserver.sin_port = htons(atoi(argv[3])); /* server port */

/* Establish connection */

if (connect(sock,

(struct sockaddr *) &echoserver,

sizeof(echoserver)) < 0) {

Die("Failed to connect with server");

}

As with creating the socket, the attempt to establish a connection will return -1 if the attempt fails. Otherwise, the socket is now ready to accept sending and receiving data.

Now that the connection is established, we are ready to send

and receive data. A call to send() takes as

arguments the socket handle itself, the string to send, the

length of the sent string, and a flag argument. Normally the

flag is the default value 0. The return value of the

send() call is the number of bytes successfully

sent.

/* Send the word to the server */

echolen = strlen(argv[2]);

if (send(sock, argv[2], echolen, 0) != echolen) {

Die("Mismatch in number of sent bytes");

}

/* Receive the word back from the server */

fprintf(stdout, "Received: ");

while (received < echolen) {

int bytes = 0;

if ((bytes = recv(sock, buffer, BUFFSIZE-1, 0)) < 1) {

Die("Failed to receive bytes from server");

}

received += bytes;

buffer[bytes] = '\0'; /* Assure null terminated string */

fprintf(stdout, buffer);

}

The rcv() call is not guaranteed to get

everything in-transit on a particular call--it simply blocks until

it gets something . Therefore, we loop until we have gotten

back as many bytes as were sent, writing each partial string as we

get it. Obviously, a different protocol might decide when to

terminate receiving bytes in a different manner (perhaps a

delimiter within the bytestream).

Calls to both send() and recv() block

by default, but it is possible to change socket options to allow

non-blocking sockets. However, this tutorial will not cover details

of creating non-blocking sockets, nor such other details used in

production servers as forking, threading, or general asynchronous

processing (built on non-blocking sockets).

At the end of the process, we want to call close()

on the socket, much as we would with a file handle

fprintf(stdout, "\n");

close(sock);

exit(0);

}

A socket server is a bit more complicated than is a client, mostly because a server usually needs to be able to handle multiple client requests. Basically, there are two aspects to a server: handling each established connection, and listening for connections to establish.

In our example, and in most cases, you can split the handling

of a particular connection into support function--which looks

quite a bit like a TCP client application does. We name that

function HandleClient() .

Listening for new connections is a bit different from client

code. The trick is that the socket you initially create and bind

to an address and port is not the actually connected socket. This

initial socket acts more like a socket factory, producing new

connected sockets as needed. This arrangement has an advantage in

enabling fork'd, threaded, or asynchronously dispatched handlers

(using select() ); however, for this first tutorial we

will only handle pending connected sockets in synchronous order.

Our echo server starts out with pretty much the same few

#include s as the client did, and defines some

constants and an error handling function:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#define MAXPENDING 5 /* Max connection requests */

#define BUFFSIZE 32

void Die(char *mess) { perror(mess); exit(1); }

The BUFFSIZE constant limits the data sent per

loop. The MAXPENDING constant limits the number of

connections that will be queued at a time (only one will be

serviced at a time in our simple server). The

Die() function is the same as in our client.

The handler for echo connections is straightforward. All it

does is receive any initial bytes available, then cycle through

sending back data and receiving more data. For short echo strings

(particularly if less than BUFFSIZE ) and typical

connections, only one pass through the while loop

will occur. But the underlying sockets interface (and TCP/IP)

does not make any guarantees about how the bytestream will be

split between calls to recv() .

void HandleClient(int sock) {

char buffer[BUFFSIZE];

int received = -1;

/* Receive message */

if ((received = recv(sock, buffer, BUFFSIZE, 0)) < 0) {

Die("Failed to receive initial bytes from client");

}

/* Send bytes and check for more incoming data in loop */

while (received > 0) {

/* Send back received data */

if (send(sock, buffer, received, 0) != received) {

Die("Failed to send bytes to client");

}

/* Check for more data */

if ((received = recv(sock, buffer, BUFFSIZE, 0)) < 0) {

Die("Failed to receive additional bytes from client");

}

}

close(sock);

}

The socket that is passed in to the handler function is one that already connected to the requesting client. Once we are done with echoing all the data, we should close this socket; the parent server socket stays around to spawn new children, like the one just closed.

As we outlined before, creating a socket has a bit different

purpose for a server than for a client. Creating the socket has

the same syntax it did in the client; but the structure

echoserver is setup with information about the server

itself, rather than about the peer it wants to connect to.

You usually want to use the special constant

INADDR_ANY to enable receiving client request on any

IP address the server supplies; in principle, such as in a

multi-hosting server, you could specify a particular IP address

instead.

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

int serversock, clientsock;

struct sockaddr_in echoserver, echoclient;

if (argc != 2) {

fprintf(stderr, "USAGE: echoserver <port>\n");

exit(1);

}

/* Create the TCP socket */

if ((serversock = socket(PF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_TCP)) < 0) {

Die("Failed to create socket");

}

/* Construct the server sockaddr_in structure */

memset(&echoserver, 0, sizeof(echoserver)); /* Clear struct */

echoserver.sin_family = AF_INET; /* Internet/IP */

echoserver.sin_addr.s_addr = htonl(INADDR_ANY); /* Incoming addr */

echoserver.sin_port = htons(atoi(argv[1])); /* server port */

Notice that both IP address and port are converted to network

byte order for the sockaddr_in structure. The reverse

functions to return to native byte order are ntohs()

and ntohl() . These functions are no-ops on some

platforms, but it is still wise to use them for cross-platform

compatibility.

Whereas the client application connect() 'd to a

server's IP address and port, the server bind() 's to

its own address and port:

/* Bind the server socket */

if (bind(serversock, (struct sockaddr *) &echoserver,

sizeof(echoserver)) < 0) {

Die("Failed to bind the server socket");

}

/* Listen on the server socket */

if (listen(serversock, MAXPENDING) < 0) {

Die("Failed to listen on server socket");

}

Once the server socket is bound, it is ready to

listen() . As with most socket functions, both

bind() and listen() return -1 if they

have a problem. Once a server socket is listening, it is ready to

accept() client connections, acting as a factory for

sockets on each connection.

Creating new sockets for client connections is the crux of a

server. The function accept() does two important

things: it returns a socket pointer for the new socket; and it

populates the sockaddr_in structure pointed to,

in our case, by echoclient .

/* Run until cancelled */

while (1) {

unsigned int clientlen = sizeof(echoclient);

/* Wait for client connection */

if ((clientsock =

accept(serversock, (struct sockaddr *) &echoclient,

&clientlen)) < 0) {

Die("Failed to accept client connection");

}

fprintf(stdout, "Client connected: %s\n",

inet_ntoa(echoclient.sin_addr));

HandleClient(clientsock);

}

}

We can see the populated structure in echoclient

with the fprintf() call that accesses the client IP

address. The client socket pointer is passed to

HandleClient() , which we saw at the start of this

section.

Python's standard module socket provides almost

exactly the same range of capabilities you would find in C

sockets. However, the interface is generally more flexible,

largely because of the benefits of dynamic typing. Moreover, an

object-oriented style is also used. For example, once you create

a socket object, methods like .bind() ,

.connect() , and .send() are methods of

that object, rather than global functions operating on a socket

pointer.

At a higher level than socket , the module

SocketServer provides a framework for writing

servers. This is still relatively low level, and higher-level

interfaces are available for server of higher-level protocols,

e.g. SimpleHTTPServer , DocXMLRPCServer ,

or CGIHTTPServer .

Let us just look at the complete client, then make a few remarks:

#!/usr/bin/env python

"USAGE: echoclient.py <server> <word> <port>"

from socket import * # import *, but we'll avoid name conflict

import sys

if len(sys.argv) != 4:

print __doc__

sys.exit(0)

sock = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM)

sock.connect((sys.argv[1], int(sys.argv[3])))

message = sys.argv[2]

messlen, received = sock.send(message), 0

if messlen != len(message):

print "Failed to send complete message"

print "Received: ",

while received < messlen:

data = sock.recv(32)

sys.stdout.write(data)

received += len(data)

print

sock.close()

At first brush, we seem to have left out some of the error

catching code from the C version. But since Python raises

descriptive errors for every situation that we checked for in the

C echo client, we can let the built-in exceptions do our work for

us. Of course, if we wanted the precise wording of errors that we

had before, we would have to add a few

try / except clauses around the calls to

methods of the socket object.

While shorter, the Python client is somewhat more powerful.

Specifically, the address we feed to a .connect()

call can be either a dotted-quad IP address or a symbolic name,

without need for extra lookup work, e.g.:

$ ./echoclient.py 192.168.2.103 foobar 7

Received: foobar

$ ./echoclient.py fury.gnosis.lan foobar 7

Received: foobar

We also have a choice between the methods .send()

and .sendall() . The former sends as many bytes as it

can at once, the latter sends the whole message (or raises an

exception if it cannot). For this client, we indicate if the

whole message was not sent, but proceed with getting back as much

as actually was sent.

The simplest way to write a echo server in Python is using the

SocketServer module. It is so easy as to almost seem

like cheating. In later panels, we will spell out the lower-level

version, that follows the C implementation. For now, let us see

just how quick it can be:

#!/usr/bin/env python

"USAGE: echoserver.py <port>"

from SocketServer import BaseRequestHandler, TCPServer

import sys, socket

class EchoHandler(BaseRequestHandler):

def handle(self):

print "Client connected:", self.client_address

self.request.sendall(self.request.recv(2**16))

self.request.close()

if len(sys.argv) != 2:

print __doc__

else:

TCPServer(('',int(sys.argv[1])), EchoHandler).serve_forever()

The only thing we need to provide is a child of

SocketServer.BaseRequestHandler that has a

.handle() method. The self instance has

some useful attributes, such as .client_address , and

.request which is itself a connected socket object.

If we wish to do it "the hard way"--and gain a bit more fine-tuned control, we can write almost exactly our C echo server in Python (but in fewer lines):

#!/usr/bin/env python

"USAGE: echoserver.py <port>"

from socket import * # import *, but we'll avoid name conflict

import sys

def handleClient(sock):

data = sock.recv(32)

while data:

sock.sendall(data)

data = sock.recv(32)

sock.close()

if len(sys.argv) != 2:

print __doc__

else:

sock = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM)

sock.bind(('',int(sys.argv[1])))

sock.listen(5)

while 1: # Run until cancelled

newsock, client_addr = sock.accept()

print "Client connected:", client_addr

handleClient(newsock)

In truth, this "hard way" still isn't very hard. But as in the

C implementation, we manufacture new connected sockets using

.listen() , and call our handler for each such

connection.

The server and client presented in this tutorial are simple,

but they show everything essential to writing TCP sockets

applications. If the data transmitted is more complicated, or the

interaction between peers (client and server) is ore sophisticated

in your application, that is just a matter of additional

application programming. The data exchanged will still follow the

same pattern of connect() and bind() ,

then send() 's and recv() 's.

One thing this tutorial did not get to, except in brief summary at the start, is usage of UDP sockets. TCP is more common, but it is important to also understand UDP sockets as an option for your application. Part two of this tutorial will look at UDP, as well as implementing sockets applications in Python, and some other intermediate topics.

A good introduction to sockets programming in C, is Michael J. Donahoo and Kenneth L. Calvert, TCP/IP Sockets in C , Morgan-Kaufmann, 2001; ISBN: 1-55860-826-5.

Please let us know whether this tutorial was helpful to you and how we could make it better. We'd also like to hear about other tutorial topics you'd like to see covered.

For questions about the content of this tutorial, contact the author, David Mertz, at [email protected] .